Paintings in an exhibition: change metaphors and a couple of views on leadership.

Main Page 7 Comments »A recent visit to the Art Gallery of NSW was, as always, an interesting few hours and a cause for reflection about how a number of themes come together in relation to change and the way we deal with it. Most importantly, it set me thinking about some leadership behaviours.

Words in an instantly recognisable typeface provide a glimpse of familiarity in a sea of change.

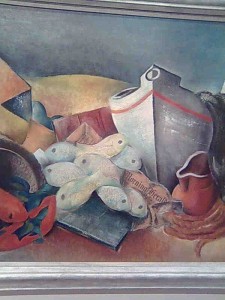

In this painting by Sali Herman, the Sydney Morning Herald masthead, from the 1940s, is juxtaposed with some freshly caught fish. Sixty or more years separate freshness which will surely fade fast from an icon which persists. Change happens yet we always have the possibility to retain vestiges of the past. This is how it should be.

In leadership, we must always remember that we are at any moment poised precariously between our past and our future. The immediate needs of a fresh catch, sit alongside the knowledge that there will be those trappings of our existence which will persist long past the time when some of the immediate intents of our endeavours have been consumed or rotted away.

Therefore, when reacting to emergent need, we should always try to retain a view which ‘looks both ways’ and which has a sense of desire to ensure that any icons which endure from this present do so because they represent a purpose which is still current and meaningful, years down the track.

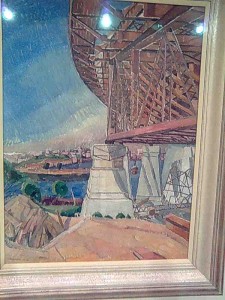

Sometimes, the thought of the function and existence of the finished product leads us to forget, or discount the processes of creation.

The Sydney Harbour Bridge must have been a massive dominator of the Sydney skyline in the late 1920s: reaching out tentatively from both shores to finally nudge together way up above the ‘big smoke’ of the city and its bustling harbour. Huge tracts of housing at both its Southern and Northern ends bulldozed to provide the approaches, and tunnels bored within the sandstone waited to feel the rush of air and the trundle of trains and trams.

The Sydney Harbour Bridge must have been a massive dominator of the Sydney skyline in the late 1920s: reaching out tentatively from both shores to finally nudge together way up above the ‘big smoke’ of the city and its bustling harbour. Huge tracts of housing at both its Southern and Northern ends bulldozed to provide the approaches, and tunnels bored within the sandstone waited to feel the rush of air and the trundle of trains and trams.

The leadership of this massive project must have needed a huge team to manage the complexities of building something on such a vast scale and to promote a shared belief in the value of the intended outcome and of the need for care and precision in the building. Huge arcs of steel, supported by cables anchored deep in the sandstone, eventually settling together, complete, high above the water.

It can be easy to think of great leadership as the qualities which enable a person to take large numbers with them as they move toward an objective which is seen to represent a national interest, or loyalty, or a grand endeavour.

Dominating one of the galleries at the NSW Art Gallery is a huge canvas by Edouard Detaille entitled ‘Vive l’empereur’ which depicts Hussars galloping in a full charge, bugles sounding, sabres swinging, toward the Russian lines in the battle of Friedland in 1806.

The notes posted beside this enormous painting point out that Detaille had set out to

“Recapture the appearance of the men of his period as they went to their death covered in gold braid.”

It is sobering to think through the psyche which led men to see themselves as taking part in a ritual of warriors, where manhood can be seen as a status symbolised by the willingness to rush headlong into battle for worthy causes: accepting the very real possibility of death as a consequence of honouring the traditions of gender, race, culture or religion. A faith in the ‘righteousness’ of the need to win a battle was enough to circumvent the natural shrinking from those things which would otherwise seek to overwhelm us.

It is sobering to think through the psyche which led men to see themselves as taking part in a ritual of warriors, where manhood can be seen as a status symbolised by the willingness to rush headlong into battle for worthy causes: accepting the very real possibility of death as a consequence of honouring the traditions of gender, race, culture or religion. A faith in the ‘righteousness’ of the need to win a battle was enough to circumvent the natural shrinking from those things which would otherwise seek to overwhelm us.

We should choose very carefully when it comes to selecting any pursuit where the need to ‘win’ becomes a significant justification for asking others to follow into places where there is danger and the possibility of very real risk.

There are those who still speak of ‘leading by example,’ of ‘not expecting anyone to do that which you are not prepared to do yourself.’ There are certainly times where this may be necessary but, as with language, behaviour and leadership: there will be times where it is better to ‘lead from behind’

Nelson Mandela says: “It is better to lead from behind and to put others in front, especially when you celebrate victory when nice things occur. You take the front line when there is danger. Then people will appreciate your leadership. “

Mandela had spent long afternoons herding cattle. His mother owned some cattle of her own, but there was a collective herd belonging to the village that he and other boys would look after. He then explained to me the rudiments of herding cattle.

“You know, when you want to get the cattle to move in a certain direction, you stand at the back with a stick, and then you get a few of the cleverer cattle to go to the front and move in the direction that you want them to go. The rest of the cattle follow the few more-energetic cattle in the front, but you are really guiding them from the back.”

He paused. “That is how a leader should do his work.” (Richard Stengel)

Clearly, there are challenges to face when it comes to changing leadership style to suit the context. Our natural sense of who and what we are; of how we see ourselves from the inside out, will have an impact.

It’s hard to lead a cavalry charge if you think you look funny on a horse. Adlai Stevenson

Drawing some of these threads together with, hopefully, some relevance for leaders in schools, maybe there are some key messages:

- Within what we do there are some things which, while pressing and immediate now will be gone in time. There are others which may seem now to only have a secondary function but which may still be there in decades to come: still recognisable and an icon of familiarity. Within our work, try to maintain an awareness of not only the rearview mirror, but also the vast horizon of possibility in front.

- We need to be clear about what we stand for and what it is that we believe would be a good possible future.

- Large products do not come about overnight, but can be years in the planning and construction. This requires leadership which builds teams and co-ordinates, provides feedback and in general keeps all committed to the intended outcomes. Our work in building something new may mean that we have to leave some things behind.

- Symbolic leadership, achieved with horn blasts and the smell of fear and the sound of thundering hooves, may be appropriate in certain circumstances, but must always be questionable when it is predicated on blind faith in ‘righteousness.’

- While it can be hugely difficult to let go and sit back, there is a massive satisfaction to be had from ‘leading from behind.’

Please feel free to click up the top where it says Comments and add your thoughts.

Recent Comments